Part 1 The Pandemic Agreement: A Turning Point for Global Health Equity and Security?

After more than three years of intense negotiations, the agreement is a step forward. But does it truly advance global health equity or risk repeating past mistakes?

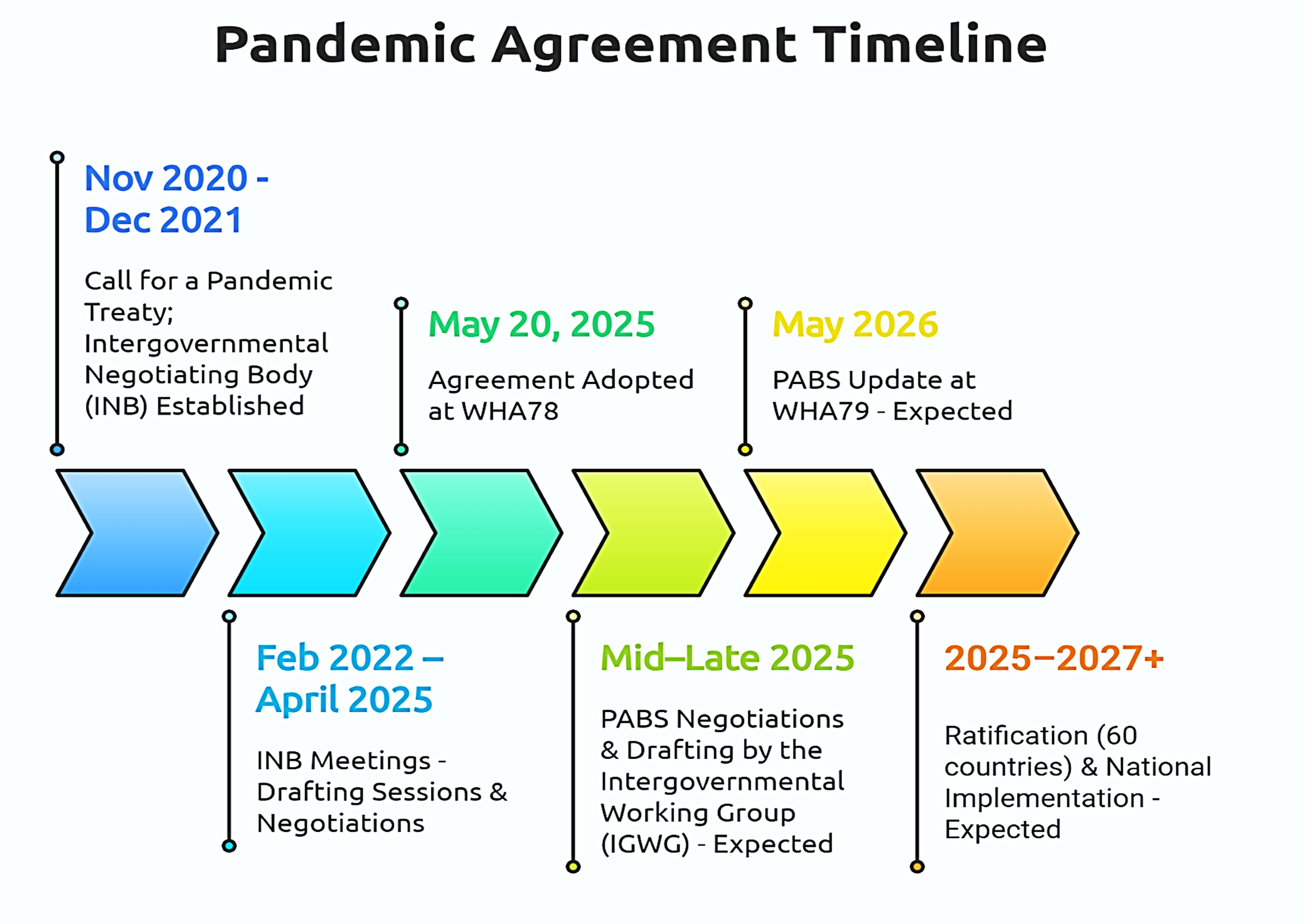

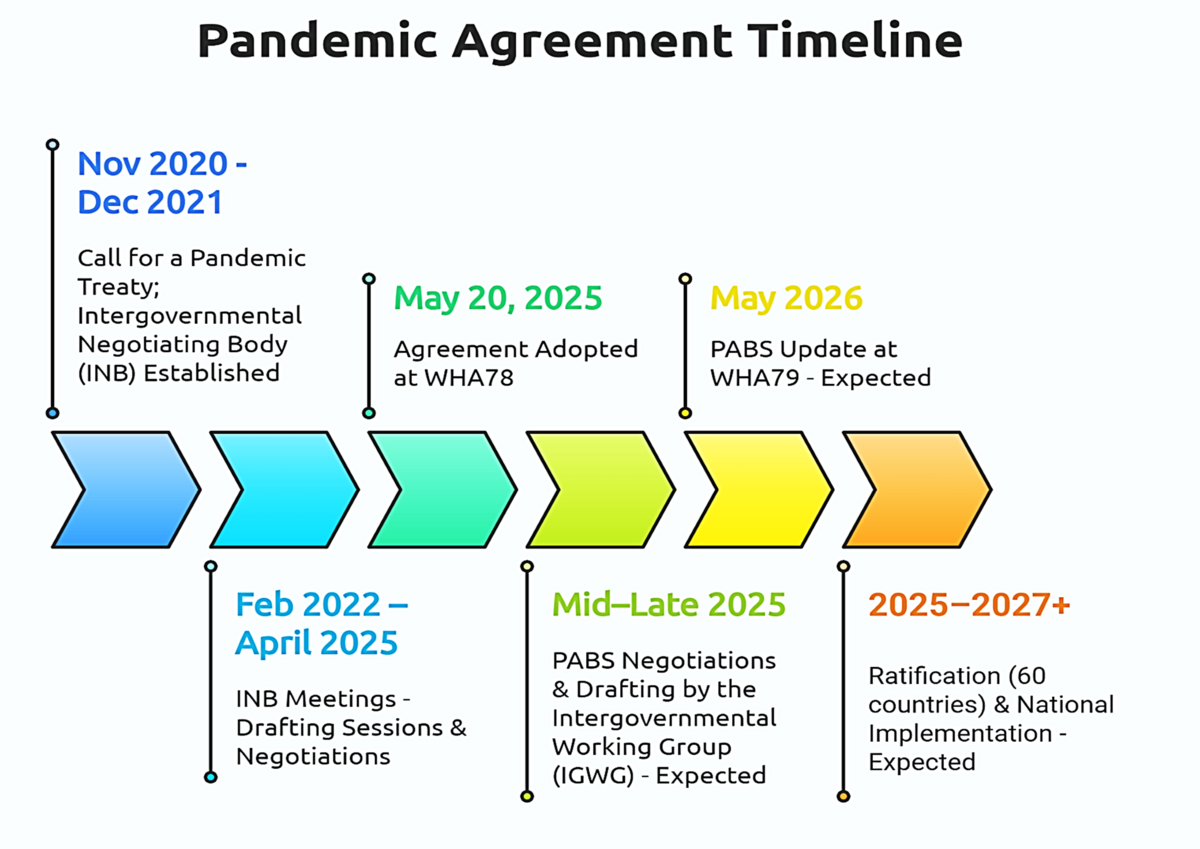

On May 20, 2025, history was made. The 78th World Health Assembly adopted the long-awaited Pandemic Agreement, a multilateral framework designed to guide the world in preventing, preparing for, and responding to future pandemics. After over three years of intense negotiations and deep global reflection following COVID-19, the agreement marks an ambitious step forward. But does it truly advance global health equity or risk repeating the same mistakes?

For the first part of our two-part article series, we spoke with Melissa Scharwey from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and Valentina Voican from the German Federal Ministry of Health (BMG).

Their perspectives, grounded in policy, practice, and front-line public health, offer a deeper look into what this agreement delivers, where it still falls short, and what comes next.

A Global Milestone, But Only the Beginning

“It was a success,” says Valentina Voican from the German Federal Ministry of Health, who was part of Germany’s team within the broader EU27 negotiation team led by the European Commission. She notes that reaching consensus was especially remarkable given the relatively short three-year timeline as compared to other international agreements. “But it is not the end of this process,” she adds. While the adoption of the agreement is a crucial first step, the annex on Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing (PABS) still has to be negotiated. The PABS system is meant to ensure that countries sharing pathogen samples also receive fair access to medical countermeasures such as vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics.

The agreement represents a compromise negotiated under pressure. “If everyone is equally unhappy, then we're on the right track,” Valentina reflects. While Germany would have preferred stronger provisions on prevention, she sees the inclusion of the One Health approach for the first time in a binding international agreement as a major win. Other important elements include articles on health system strengthening, health workforce as well as the establishment of a global supply chain and logistics network. Crucially, the process proved that multilateralism and solidarity remain possible, even in a fragmented global landscape. Still, Valentina highlights one key shortcoming, accountability in the implementation of the agreement: “It would have been helpful to include binding regulations on implementation and compliance,” she notes.

From MSF’s perspective, the treaty reflects both progress and limitations. “We can't say it’s the biggest milestone ever achieved, but it's also not a complete missed opportunity. The truth lies somewhere in between,” says Melissa Scharwey, Humanitarian Advocacy Officer for Global Health and Access to Medical Tools at Médecins Sans Frontières. She was an active part of MSF’s team involved in the advocacy around the negotiation process. Her work focused on equitable access to vaccines, medicines, and diagnostics, as well as the provisions protecting healthcare workers and vulnerable groups, particularly in humanitarian settings.

MSF welcomed key provisions such as prioritizing health workers, ensuring humanitarian access, and protecting clinical trial participants, but had hoped for firmer commitments, especially around technology transfer and public funding conditions. “We have a better base now,” she says. “But we’re not done.” If she could add one clause, it would be a clear commitment that governments “prioritize global equity over profits”, especially when public funding supports medical research. “We can’t keep repeating the same mistakes. MSF teams are seeing over and over again, how inequitable the access to lifesaving medical tools has been. And we also know this hinders an effective response to pandemics” she warns.

One Health: Enshrined, But Requires Action

A major breakthrough in the agreement is its explicit inclusion of the One Health approach, which considers the health of humans, animals, and the environment and their interrelationships. Although Germany would have preferred a stronger and more detailed section on One Health (Article 5), Valentina from BMG calls it a “great success” that the concept is anchored in the text, the first time in such an international agreement.

By embedding One Health, the agreement promotes integrated surveillance and cross-sector collaboration to detect and prevent outbreaks at their source. “I really hope that this will form the basis for further discussions and collaboration,” says Valentina. Over time, this could drive countries to invest in veterinary surveillance, climate-related health research, and other preventive measures that strengthen pandemic preparedness at its roots.

Germany has long been committed to One Health on the international stage such as its partnership with France on the German-France One Health Approach. The agreement addresses several diplomatic priorities of Germany and the EU, including early warning systems, monitoring, and capacity building.

The Equity Challenge: Voluntary vs Binding

The agreement includes a commitment for pharmaceutical manufacturers to allocate 20% of real-time pandemic production to the WHO for distribution to countries in need – at least half of which should be donated. Despite all its strong language on equity, major criticisms remain, especially around sharing vaccines and transfer of technology (Article 11). In the final version, many equity measures remain voluntary. Some call it an “empty shell,” while others see a “foundation to build on.”

For MSF and other civil society organisations, this is a red flag. The language around technology transfer – encouraging companies to share know-how or intellectual property (IP) – remains weak. “We’re relying on the goodwill of pharmaceutical companies to ensure equitable access… and COVID has shown that that’s not enough,” says Melissa. “What we have now […] leaves the world largely at the discretion of private rights holders. And that is definitely a risk.”

Why no binding clauses? In part due to pushback from high-income countries with strong pharma sectors.

Valentina acknowledges Germany’s firm stance on protecting innovation and IP. “It’s important to have a strong pharmaceutical industry that can help us during the next pandemic […]. We need to give them the room to be innovative […]. The compromise we found provides the right balance” she says. The EU position was that Research and Development (R&D) incentives – including IP protections – are essential to enable fast innovation.

But not everyone agrees. Melissa from MSF argues that IP is not the main driver of innovation, particularly in global health. “We can't forget the amount of public funding that goes into biomedical research and development,” she says. “The idea that IP alone is the driver of innovation, from our experience, is not true; On one hand, we are repeatedly witnessing how IP monopolies result in barriers to access to medical innovations for the people MSF cares for. On the other hand, there is a research gap for diseases that don’t promise high profits, but affect millions.” She stresses the need to get the narrative right: failing to share IP and technology undermines public investment efficiency.

For MSF, the lack of binding commitments exposes a double standard. Countries like Germany support global health for example through research investments but held firm red lines in the treaty negotiations that weakened more progressive provisions. The tension between public health priorities and commercial interests remains unresolved.