Part 2: Global Health Under Pressure: Prioritizing Universal Health Cover-age and the role of civil society at the G20

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/user_upload/Design_ohne_Titel__11_.png)

In our article series "Global Health Under Pressure," we examine the effects of U.S. funding cuts in development cooperation and changes in global health architecture on key issues in global health. We speak with experts from academia, politics, and international cooperation. Today's article focuses on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the role of civil society in the G20 process. General information on UHC can be found in Part 1.

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) aims to provide all people with equal access to appropriate quality health services without causing financial hardship.¹ UHC is a central goal of the 2030 Agenda and is enshrined in SDG Target 3.8. Outbreaks of HIV/AIDS, COVID-19, and Ebola have made us realize what it means when this access is not granted and how important resilient health systems are. When health systems lack funding to achieve UHC, the most vulnerable populations suffer. Despite this, healthcare and UHC are not a global priority at the moment. Political developments in the U.S. are even obstructing global health justice. In light of these challenges, it is encouraging that South Africa, during its G20 presidency, has prominently placed UHC and Primary Health Care (PHC) on the G20 health agenda. The question, however, is how UHC can remain a priority and be sustainably funded in the long term, especially in politically uncertain times for global health.

How should UHC financing look in the future?

The immense funding gap left by the U.S. withdrawal from global health is difficult to fill by other donors—especially as the trend in many countries is shifting towards cutting ODA (official development assistance) in favor of increasing security spending. While some philanthropic foundations, like the Gates Foundation, are increasing their contributions, even this will not be enough to cover the deficit. The effects of this trend are also being felt in the area of UHC.

Dr. Magda Robalo, former Health Minister of Guinea-Bissau, is currently Co-Chair of the UHC2030 Steering Committee, Interim Executive Director of Women in Global Health, and President and Co-Founder of the Institute for Global Health and Development. She has spent her entire career working on the lack of access to basic health services and the associated vulnerability of disadvantaged populations. In an interview with us, she explains what she believes is necessary to sustainably finance UHC even in times of political crisis: "If you do not reform the global financial infrastructure, the IMF, the World Bank, and the way loans are granted, you will not be able to generate money for investments in health. If you do not ensure that economies grow or continue to grow, we will not be able to invest in health." For her, domestic resources are a critical factor for sustainable health financing. However, she believes that in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), economic growth of four to five percent is required. The new Lancet Report Global Health 2050 highlights that in low-income countries, 5% of GDP must be spent on health in order to achieve UHC.²

How is the international community engaging with UHC?

Challenges in development cooperation and the health sector are not new. With many different donors, multilateral organizations, and initiatives, the commitment to global health has been fragmented, leading to inefficient parallel structures, including in the area of UHC. In 2007, the World Bank and WHO launched the International Health Partnerships (IHP+). This initiative was supported by key organizations such as UNICEF, UNAIDS, Gavi, the Global Fund, as well as NGOs and various countries. In 2016, IHP+ was expanded to UHC2030 to focus on strengthening health systems and achieving universal health coverage.

UHC2030

UHC2030 operates as a multi-stakeholder platform on three levels: through advocacy work, it influences political, economic, and social decision-makers, it tracks the implementation of measures, policies, and programs in the area of UHC to ensure accountability, and it fosters increased collaboration among various stakeholders for information exchange and alignment with national strategies. Dr. Robalo emphasizes the relevance of multilateralism in this context. While countries develop their own health strategies and maintain sovereignty in political decisions, international compromises are essential for living together in our globalized world. However, she also points out that the multilateral system as we know it could face limits due to current political developments. For example, Dr. Robalo notes that the United Nations is losing influence. These trends also pose a danger to universal health coverage. The multilateral system has reached a point where it needs to be fundamentally changed. She recommends consolidating global health initiatives and working on a new governance structure, especially as the trend leans towards increasing nationalism. Innovative approaches are now needed to strengthen multilateral cooperation.

South Africa's G20 Presidency

The health agenda of South Africa's G20 presidency also focuses on strengthening multilateralism. Under the theme "Solidarity, Equality, Sustainability," UHC and PHC are at the heart of the Health Working Group. In addition to strengthening universal health coverage through primary health care, other priorities discussed this year include: promoting health workforce resources, tackling non-communicable diseases (NCDs), pandemic prevention preparedness and response (PPPR), and science and innovation for health and economic growth.

At the second meeting of the Working Group, South Africa's Health Minister, Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi, emphasized the importance of countries reallocating their resources to prioritize health services. Innovative financing mechanisms are crucial to filling the current gaps. He also pointed to the worrying trend that funding for global health is decreasing while the costs for health services are rising. The results of the Working Group will feed into discussions at the G20 Health Ministers' meeting in November 2025, as well as into the subsequent declaration.

The U.S. engagement within the G20 and the G20 Health Track remains unclear. U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio was absent from the Foreign Ministers' meeting, which marked the start of South Africa’s G20 presidency. However, at the recent meeting between South African President Cyril Ramaphosa and US President Donald Trump, Trump announced that he might attend the G20 summit after all.

Civil Society Participation in the G20 Process: Showcase Politics?

The involvement of civil society perspectives in G20 decisions is mainly driven by the Civil Society 20 (C20) initiative. Unlike the G20 (and G7), the C20 is not made up exclusively of civil society actors from G20/G7 member states but is also open to participants from other countries. A first meeting of the C20 Global Health Working Group has not taken place during the first trimester of 2025. Even during the initial meetings of the G20 Health Working Group, there have been no statements from civil society. However, it is certain that this civil society working group will exist, as reported to us by Marwin Meier. He is a political advisor for health and migration at World Vision, with over 20 years of experience in the health sector across various civil society organizations. Initially, he worked for ADRA (Adventist Development and Relief Agency) as a country director in Togo and the Philippines. He then joined World Vision, first working on HIV/AIDS and later on maternal and child health. He has been actively involved in the C20 processes since 2007 and has participated in three Sherpa processes.

After three Sherpa meetings, explains Marwin Meier, 80% of the final communiqué has already been negotiated. Only then do consultations with civil society take place.

The C20 or C7 summits, are often scheduled so close to the G20 Summits that real consultation and participation become impossible. In 2015, the C20 Summit took place at the Bavarian Embassy, with even Chancellor Merkel attending—but due to her schedule, the meeting was held just one week before the G20 Summit. Often, heads of state and government are not even present at civil society summits.

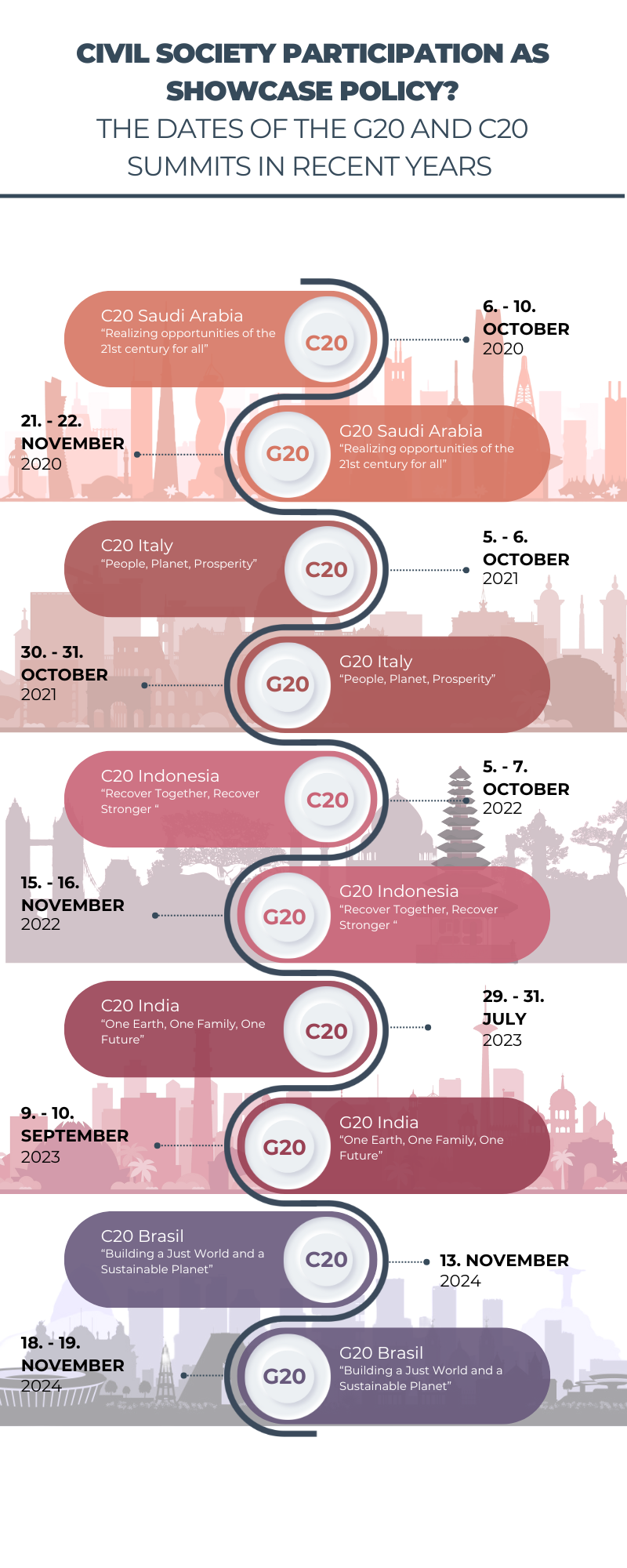

The graphic shows that, at best, civil society summits take place 1.5 months before the G20 Summits. This leaves little time for thoroughly reviewing civil society’s recommendations and outcomes—especially since negotiations in the multilateral system take a significant amount of time.

Challenges for Civil Society Engagement in the G20 and G7 Process

The civil society of the host country is responsible for organizing the civil society summit. This means that in addition to their usual schedules, they must also consider the specific timelines of the global event. This is particularly challenging in a sector that is continuously dealing with resource shortages.

However, Marwin Meier considers it a positive aspect, that the BMZ (Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development) has co-financed the C7 in recent years. This allowed for a full-time position within civil society to manage the organization of the C7. According to their own statements, the BMZ is actively working to involve civil society in the G20 processes.

Sustainable use of institutional knowledge is also a challenge. In the last 25 years, the G20 Summit has taken place twice in Germany (and the G7 Summit three times). In the meantime, a lot of institutional knowledge is lost, as Marwin Meier explains.

Also, under this year’s South African G20 presidency, civil society is organizing itself, according to Marwin Meier. “There is a well-organized civil society in South Africa, but this is by no means always the case, and there is unfortunately also political hijacking,” he criticizes. For example, during India’s G20 presidency in 2023, the organization that had been chosen by civil society as the host was dismissed. Instead, the government appointed a government-affiliated university as the C20 host. Civil society in India then founded its own People20 but suffered massive repression. The police were present at the meetings, the third day of the gathering was canceled without explanation, and international civil society was not allowed to attend the meeting, even though they had traveled.

How well the C20 process will be organized this year is still uncertain. However, Marwin Meier can already make some predictions about the content: In the area of UHC, civil society is usually very focused on Primary Health Care and Community Health. He expects that these issues will be a key focus for civil society this year, with a focus on marginalized groups. In his view, the African context will likely address “high-risk groups” such as LGBTQIA*. He also expects reproductive health and rights, as well as pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response, and patents to be topics on the civil society agenda. Given the political stance of the Trump administration, it may actually be an advantage for these topics if the U.S. would withdraw from the G20 process.

¹WHO (2025): Universal health coverage (UHC). www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc)

²Global health 2050: the path to halving premature death by mid-century